For centuries, Russian writers, politicians, philosophers, and rulers have struggled with the question of Russia’s European-ness. Is Russia European? Should western culture be allowed to influence Russians and Russian culture? Given the current political climate, the issue of Russia versus the West is an incredibly relevant topic that has a long, complicated story, and is arguably at the center of Russian history. The extent and limitations of European influences are readily apparent in the history of the Russian language.

Figure 1 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/attachments/images/large/europe-political.jpg?1547145650 |

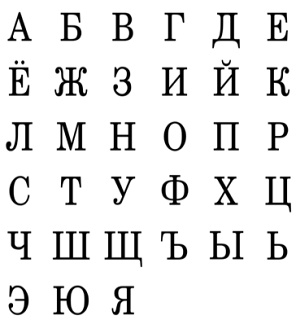

Russia did not start out “European.” Situated between the edge of Europe and Central Asia, Russian culture is a truly fascinating, unpredictable product of the convergence of many different histories. Many people already know, and will remember with a hint of anxiety, that Russian has a different alphabet (it really isn’t scary! I promise!). It’s called the Cyrillic alphabet, after the Greek Saint Cyril, who created it in the 9th century for the Slavic languages.(1) The alphabet provided by Saint Cyril began a centuries-long process of changing and standardizing the Russian alphabet to suit the evolving needs of its people. Although seemingly strange for the history of what is now a major world power, from 1230 to around 1550, Russia was occupied by the Mongols from the east, and was thus cut off from the major cultural developments of the Renaissance in the west.(2) What emerged after the occupation was a distrustful, relatively uneducated Russian elite whose language bore the mark of the Mongols’ long occupation.(3)

|

Figure 2: Early Cyrillic Alphabet Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Cyrillic_alphabet |

|

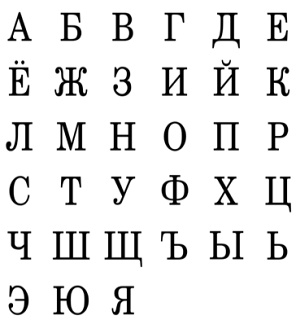

It was this elite and the Russian culture they represented that Tsar Peter the Great, who had spent much of his youth among Europeans, set out to dramatically reform during his reign from 1682 to 1725. He despised Moscow, Russia’s capital, for what he saw as its “backwardness”- its people were unrefined, uneducated, and suspicious of foreigners.(4) His policies to counteract this ranged from weird to dramatically altering the course of Russian history. When he wasn’t busy building his dream European city (St. Petersburg) in the middle of a swamp technically owned by their Swedish enemies, he ordered male members of the aristocracy to shave their beards.(5) He also introduced changes to the Cyrillic alphabet, collectively called the “civil script,” which consisted of replacing and discarding old characters in favor of something that more closely resembled the Latin alphabet (The Russian Cyrillic alphabet was once again revised in January 1918, with the removal of several “redundant” letters).(6)

|

| Figure 3: Modern Russian Cyrillic Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/00Russian_Alphabet_3.svg/1149px-00Russian_Alphabet_3.svg.png |

Unfortunately for the Russian language, this was about all the attention Peter the Great paid to it over the course of his rule. His European vision of Russia meant the aristocracy was to learn French and other foreign languages.(7) By the 1800s, Russian nobles struggled to speak Russian, and Russian literature and vocabulary were severely lacking.(8) Many words were (and still are) borrowed from French, such as muzei/musée (museum), café, and etazh/étage (building floor). The written Russian that did exist was not standardized and based on “archaic Church Slavonic,” meaning it did not reflect the way average Russians expressed themselves.(9) It was in this context that the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin came to the rescue of his native language’s literature. He dedicated himself not just to writing in Russian, but also to developing new words that better reflected spoken Russian.(10) For his contributions, he is revered to this day, and has been described as the father of Russian literature.(11) What followed over the course of the nineteenth century was tension between the continuation of this European influence and its rejection by authors such as Pushkin and Tolstoy, as well as the development of Russian literature with writers such as Dostoevsky and Chekhov.(12)

|

Figure 2 Alexander Pushkin Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Alexander_Pushkin_(Orest_Kiprensky,_1827).PNG |

This tension continued all the way until the Russian Revolution, when Russian’s fortunes changed. The Bolsheviks inherited a vast empire in which dozens of languages besides Russian were spoken. In the early 1920s, under Lenin, Soviet language policy was that no language should be treated as superior to the others, and that countries of the Soviet Union had the right to use and teach their native language.(13) In 1938, however, under Stalin, Russian was made a mandatory subject throughout the Soviet Union.(14) More importantly, following World War II, Russian gained traction as the result of migration and the concentration of administrative power in Moscow.(15) Over the course of the 20th century, unofficial government policy and political trends made Russian by far the dominant language of the Soviet Union. Even decades after its collapse, citizens of the former Soviet Union still typically learn Russian, a significant shift from being rejected by what should have been its native speakers.

Linguistic and language policy developments in Russia are just some of the numerous manifestations of Russia’s struggle over its identity. For various reasons, not all of them moral, Russian is now spoken in countries through Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Russian did not always, however, occupy such a predominant position. In the 1800s, pursuit of a “European” Russia resulted in the Russian language’s neglect for over a century. Writers such as Pushkin and Tolstoy took up the cause of reviving the Russian language, shaping it and, by extension, Russian culture into something future generations could be proud of.

Works Cited1. Figes, Orlando,

Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia. New York, New York: Picador, 2002.

2. Iliev, Ivan, “Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet.”

International Journal of Russian Studies, no. 2 (2013): 221-285.

3. Kirkwood, Michael, “Glasnost’, ‘the National Question’ and Soviet Language Policy.”

Soviet Studies, vol. 43 no. 1 (1991): 61-81.

4. Berdy, Michael A., “The Soviet Language Revolution.”

The Moscow Times, November 10, 2017. Accessed April 17, 2019. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2017/11/10/the-soviet-language-revolution-a59541