Let’s imagine the following situation. We have a main character named Lang and she is in a dangerous situation. One day, a candidate in a political campaign approaches Lang about her representing the very fundamental problem of our society. He brings a crowd of reporters and gives a passionate speech about Lang. She immediately becomes the most controversial topic of the election. On one hand, she is glad people are finally recognizing the issue that deserves attention, but she is also feeling overwhelmed now that people are deeply invested, and the tension keeps escalating. Lang now feels the conversation is no longer about her but something greater, and she is not sure she wants to be the catch-all term for all the problems that do not necessarily pertain to her.

The election is now over. It was a brutal fight for both the winning and losing sides. The town is trying to regain its peace. Lang notices something. On one hand, she feels free, now that the fierce debate around her is over. On the other hand, people tiptoe around her and look as if they never want to bring up the issue. She finds herself confused and asks: can I not be something in between neglected and politicized?

This anecdote could be a rough analogy for the status of the Irish language in Northern Ireland. For a while, Northern Ireland was a well-known example of an intragroup conflict that occurred over language. After the partition of the island between Ireland and Great Britain, the Irish language became a highly political issue, as it was seen on both sides of the border as a symbol of nationalist aspirations (Crowley, 2005: 180). The teaching of Irish in schools was the first focus of Ulster Unionism’s disdain for the language. By 1923, funding for the Irish language teacher-training colleges was withdrawn. Consequently, Irish as an ordinary subject was reduced to no more than an hour and a half per week to children of the third grade and higher, and Irish could only be taught as an extra subject outside school hours (Crowley, 2005: 181). This issue continued to be a focal point of Unionists’ contempt towards Nationalists, and in 1933, all fees payable for the teaching of Irish as an extra subject were finally abolished.

Nonetheless, the use of Irish in Northern Ireland by individuals was treated with suspicion and hostility and its official use was forbidden (Crowley, 2005: 182). The BBC banned the language for fifty years and the Stormont parliament proscribed street signs in Irish. On the other hand, despite the official interdiction on Irish, the language was taught in Catholic schools and fostered by voluntary organizations. After partition, a northern branch of the Gaelic league, Comhaltas Uladh, was set up in order to negotiate with education authorities on behalf of the language and it has remained active ever since. Furthermore, various organizations appeared, including Glún na Buaidhe, Fal, independent sporting clubs (as well as the Gaelic Athletic Association), an Irish-medium credit union, a shop, prayer groups such as Cuallacht Mhuire and Réalt, a choir, and various literary groups (Maguire 1991: 30-2). Unfortunately, such small-scale organizations amounted to little more than a token presence in the face of official disregard. These phenomena reinforced segregation of Nationalists and Unionists in Northern Ireland.

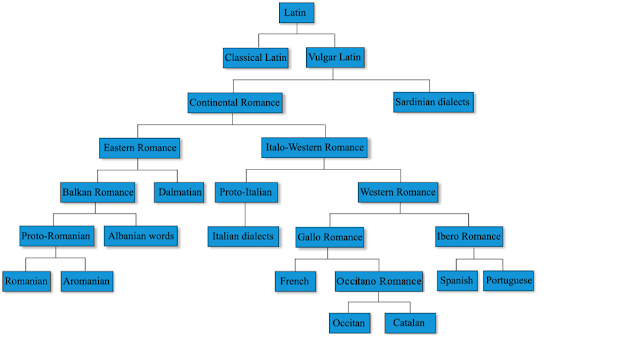

|

| Irish speakers in the 2011 census in Northern Ireland Source: Wikimedia Commons |

It is fair to say that since the 1990s, Irish has regained some of its cultural capital and has lost the stigma associated with it for so long. This in turn has fed into a second stage in favor of revitalizing the language. This stage tried not only to preserve the connection between the language and the identity of the nation, but also to accommodate growing pressures for pluralism. The Belfast Agreement became a turning point, switching stagnant and repetitive conflict into a sustainable peace process. In the section of the agreement regarding rights, safeguards, and equality of opportunity − particularly with reference to economic, social, and cultural issues − the text declared that: “All participants recognize the importance of respect, understanding and tolerance in relation to linguistic diversity, including in Northern Ireland, the Irish language, Ulster-Scots and the languages of the various ethnic minorities, all of which are part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland” (Belfast Agreement 1998: 19).

The British government declared that it would:

“take resolute action to promote the language; facilitate and encourage the use of the language in speech and writing in public and private life where there is appropriate demand; make provision for liaising with the Irish language community, representing their views to public authorities and investing complaints; place a statutory obligation on the Department of Education to encourage and facilitate Irish medium education in line with current provision for integrated education; and etc.”.Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement (1998), the promotion of the Irish language throughout the island (i.e., funding, publications, and support for Irish language education) was launched.

There are also still to this day projects going on to promote the Irish language in Northern Ireland. One notable one is the Scríobh Leabhar (Write a Book) Project. It invites students to create, design, and publish their own books in Irish. Pupils from 17 schools in Northern Ireland took part in 2016. They wrote their own stories in Irish on many subjects and awards were presented to some of the 1500 pupils from Northern Ireland in June 2016.

Another project is the East Belfast Mission. In 2015, support for three years was granted to the East Belfast Mission, which focusses on raising awareness and empowering the Protestant community regarding the Irish language. The Civil Leadership Award was presented to Linda Ervine for the work she has done for the teaching of the Irish language in the Turas Language Center of the East Belfast Mission.

A final project involves funding a community-based network for Irish Language Development Officers that implements a Program of Activities. This project aims to promote, develop and preserve Irish on a public basis. The current period started in January 2011 with a budget of up to €3.6 million. It operates at a community level in conjunction with voluntary committees who have knowledge of the local circumstances and who know Irish speakers.

The case of Northern Ireland shows us how a language can become highly politicized and promote conflict when attached to group identity. However, unlike other cases in Europe where regional groups have encouraged stronger identity in order to promote an endangered language, the case of Irish in Northern Ireland requires some separation between issues of language and identity. The Irish language in Northern Ireland will have to go through a normalization process and a process of protection and promotion simultaneously. It continues to face progress and backlash at the same time. For example, in 2015, Sinn Féin attempted to introduce an Irish language bill but failed. In the following years, the Irish language once again became the center of attention when the introduction of the Irish Language Act (Acht na Gaeilge), aimed to grant Irish equal status alongside English, reportedly led to “political deadlock in Northern Ireland”. While more than ten thousand people took to the streets of Belfast to campaign in favor of the Act, others expressed concerns and accused the protesters of politicizing the language. The Irish language in Northern Ireland will probably never be apolitical, as it embodies social and political significance for the population. However, going back to Lang in our anecdote, we should probably let her – and the language issue − continue to be a happy medium between neglect and obsession.

References

Crowley, Tony. Wars of words: the politics of language in Ireland 1537-2004. Oxford University Press on Demand, 2005.

Maguire, Gabrielle. Our own language: An Irish initiative. Vol. 66. Multilingual matters, 1991.

The Belfast Agreement, 1998

Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32680535

“Who ‘Politicised’ the Irish Language?” By Ciarán Mac Giolla Bhéin (02/14/2019) http://www.rebelnews.ie/2019/02/14/who-politicised-the-irish-language/

“Why is Irish language divisive issue in Northern Ireland?” By Jennifer O'Leary (09/2014) https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-30517834

“Irish Language Act: Laws not threatening says Welsh commissioner” By Robbie Meredith (03/15/2019) https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-47575607

“A New Protestant Beginning for the Irish Language in Belfast” http://www.pri.org/stories/2013-04-10/new-protestant-beginning-irish-language-belfast