By Kelly Mui

Argentina seems like the last place you would find Welsh speakers because of how far the original homeland of the language, Wales, is from South America. However, due to mass emigrations from the British Isles in the 19th century, there has been a relatively large community of Welsh speakers in Argentina for over 150 years.

In 1865, around 150 Welsh settlers arrived in the region of Patagonia from the city of Liverpool on the Mimosa (Johnson, 2010). The exact number of emigrants from Wales in the early years is unknown, but many more immigrants were encouraged to settle in this new Welsh colony a decade later when the Argentine government granted the newcomers ownership of their land. But why not settle in North America where large numbers of immigrants were moving in order to gain religious freedom and chase their “American dream”? The answer to this question is that some settlers felt that Welsh immigrants in North America adapted to English too much and too quickly so they decided to move to an even more isolated area where concurrence from English was not threatening their language and culture (Tweedie, 2012). The goal was to build “a Wales outside of Wales” and gain religious freedom and freedom to use their language (Why do they speak Welsh in South America?).

Settling in a new area was not an easy task. Without any knowledge of how to farm the land and, consequently, after numerous failed harvests, many settlers gave up and moved East of Argentina or to North America (Tweedie, 2012). The few who stayed found themselves rapidly outnumbered not only by Argentinians but also other immigrants. Eventually, the Argentinian government pushed for Spanish as their official language, leading to further stigma against Welsh speakers. By the 1950s, most of the Welsh speakers had given up speaking Welsh. Not only was Welsh dying out but the settlers’ traditions were also beginning to fade away.

All hope was not lost, however, as in 1965, the 100th anniversary of the Mimosa’s journey sparked a renewed interest in Welsh. The Welsh revival movement was born. From then on, there were increased efforts by the Welsh population in Patagonia and also the Welsh government in the UK to reinvigorate the language and the culture in South America (Why do they speak Welsh in South America?).

Today, Welsh culture and the outdoors are two leading themes of the tourism boom in Patagonia. Tourism, the leading economic sector in Patagonia, has also helped efforts in maintaining Welsh. But is it enough? There have been many successful campaigns leading to the revival of Welsh, but the real question is whether or not this success can last. Can Welsh in Patagonia gain durable ethnolinguistic vitality?

A study conducted by Ian Johnson in 2010 explored this question. The main focus of the study was tourism and the residents’ feelings towards tourism (Johnson, 2010). The study was conducted using a vitality questionnaire in the form of interviews. The participants were of a wide variety of professions from educators to shop owners. The participants were allowed to choose which language they wished to speak as well as the location where the interview was conducted. Johnson summarizes his results by saying that tourism is just one way in which Welsh can gain ethnolinguistic vitality. The reasoning behind this conclusion is that tourists are attracted to the “other-ness” of a Welsh-Argentinian identity which leads them to visit tourist sites. These tourist sites purposefully highlight cultural differences by having bilingual signs in Welsh and Spanish (see picture below), tea-shop owners dressed in traditional dresses, people speaking Welsh to tourists, and streets decorated with symbols unique to Welsh culture. Through these actions, Spanish-Welsh bilinguals can gain an economic advantage over the Spanish-speaking locals and thus preserve the Welsh language as well (Johnson, 2010).

Another way in which Welsh maintains its vitality is through support from the Welsh government. In recent years, Welsh language teachers were trained to live in Patagonia for one year or even longer in order to teach people the language. In recent years, a large number of religious ministers have also relocated from Wales to Patagonia to manage church and religious affairs. Besides direct support from the motherland’s government, there has also been an increase in tourists who visited Patagonia or, conversely, moved to Wales for longer periods of time, to work or even to study Welsh (Johnson, 2010). This type of transnational contact and population exchange between Wales and Patagonia also effectively increases Welsh’s ethnolinguistic vitality by showing the economic advantages that the Welsh language and culture can bring.

From Johnson’s (2010) study, it seems like Welsh is in a good place and is unlikely to die out any time soon. However, things are not perfect. Many residents have also expressed concern that while Welsh now flourishes in Patagonia, it is mainly due to support and contact with Wales, the motherland in the UK. What would happen if Wales decided to stop sending their teachers or stop providing economic support to Patagonia? A number of residents in the study doubted that their distinctive culture would be able to survive without this external support. Another concern is that English has a huge influence all over the globe and Patagonia is no exception. Numerous younger residents expressed their dilemma of language learning that sounds familiar in many minority language speaking regions around the world: put more effort into Welsh instead of English or focus on the most wide-spread international language and minimize investment of time and effort in Welsh? Most Patagonians of Welsh descent believe that maintaining the Welsh language and culture is important. However, since English holds so many commercial advantages, they also believe that they must learn English first (Johnson, 2010). These dilemmas are not limited to Welsh speakers in Patagonia. As in other regions around the world that wish to maintain their distinctive cultural heritage, dependency on external sponsorship is not a viable long-term solution for preserving ethnolinguistic vitality.

Bibliography

|

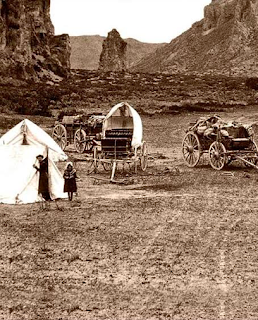

| The Mimosa, from Wikipedia |

In 1865, around 150 Welsh settlers arrived in the region of Patagonia from the city of Liverpool on the Mimosa (Johnson, 2010). The exact number of emigrants from Wales in the early years is unknown, but many more immigrants were encouraged to settle in this new Welsh colony a decade later when the Argentine government granted the newcomers ownership of their land. But why not settle in North America where large numbers of immigrants were moving in order to gain religious freedom and chase their “American dream”? The answer to this question is that some settlers felt that Welsh immigrants in North America adapted to English too much and too quickly so they decided to move to an even more isolated area where concurrence from English was not threatening their language and culture (Tweedie, 2012). The goal was to build “a Wales outside of Wales” and gain religious freedom and freedom to use their language (Why do they speak Welsh in South America?).

Settling in a new area was not an easy task. Without any knowledge of how to farm the land and, consequently, after numerous failed harvests, many settlers gave up and moved East of Argentina or to North America (Tweedie, 2012). The few who stayed found themselves rapidly outnumbered not only by Argentinians but also other immigrants. Eventually, the Argentinian government pushed for Spanish as their official language, leading to further stigma against Welsh speakers. By the 1950s, most of the Welsh speakers had given up speaking Welsh. Not only was Welsh dying out but the settlers’ traditions were also beginning to fade away.

All hope was not lost, however, as in 1965, the 100th anniversary of the Mimosa’s journey sparked a renewed interest in Welsh. The Welsh revival movement was born. From then on, there were increased efforts by the Welsh population in Patagonia and also the Welsh government in the UK to reinvigorate the language and the culture in South America (Why do they speak Welsh in South America?).

Today, Welsh culture and the outdoors are two leading themes of the tourism boom in Patagonia. Tourism, the leading economic sector in Patagonia, has also helped efforts in maintaining Welsh. But is it enough? There have been many successful campaigns leading to the revival of Welsh, but the real question is whether or not this success can last. Can Welsh in Patagonia gain durable ethnolinguistic vitality?

A study conducted by Ian Johnson in 2010 explored this question. The main focus of the study was tourism and the residents’ feelings towards tourism (Johnson, 2010). The study was conducted using a vitality questionnaire in the form of interviews. The participants were of a wide variety of professions from educators to shop owners. The participants were allowed to choose which language they wished to speak as well as the location where the interview was conducted. Johnson summarizes his results by saying that tourism is just one way in which Welsh can gain ethnolinguistic vitality. The reasoning behind this conclusion is that tourists are attracted to the “other-ness” of a Welsh-Argentinian identity which leads them to visit tourist sites. These tourist sites purposefully highlight cultural differences by having bilingual signs in Welsh and Spanish (see picture below), tea-shop owners dressed in traditional dresses, people speaking Welsh to tourists, and streets decorated with symbols unique to Welsh culture. Through these actions, Spanish-Welsh bilinguals can gain an economic advantage over the Spanish-speaking locals and thus preserve the Welsh language as well (Johnson, 2010).

Another way in which Welsh maintains its vitality is through support from the Welsh government. In recent years, Welsh language teachers were trained to live in Patagonia for one year or even longer in order to teach people the language. In recent years, a large number of religious ministers have also relocated from Wales to Patagonia to manage church and religious affairs. Besides direct support from the motherland’s government, there has also been an increase in tourists who visited Patagonia or, conversely, moved to Wales for longer periods of time, to work or even to study Welsh (Johnson, 2010). This type of transnational contact and population exchange between Wales and Patagonia also effectively increases Welsh’s ethnolinguistic vitality by showing the economic advantages that the Welsh language and culture can bring.

Bibliography

- BBC iWonder - Why do they speak Welsh in South America? (n.d.). Accessed in January 20, 2018, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/z9kr9j6

- Johnson, I. (2010). Tourism, transnationality and ethnolinguistic vitality: the Welsh in the Chubut Province, Argentina. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 31(6), 553-568. doi:10.1080/01434632.2010.511228

- Tweedie, N. (2012, March 28). The Welsh Argentine who fought the British. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/southamerica/argentina/9169222/The-Welsh-Argentine-who-fought-the-British.html

---

Kelly Mui was a senior in East Asian Languages and Cultures when she wrote this text in 418, ‘Language and Minorities in Europe’ in spring 2017.

I thought this blogpost highlighted an interesting point that is sometimes forgotten in when talking about people learning a lingua franca: People feel that when they are not putting all their efforts at learning a language solely into the lingua franca, that they will be disadvantaged. Thus, smaller languages end up suffering because they are seen as less important to learn compared to the lingua franca.

ReplyDeleteWhat is often forgotten however in this discussion is that precisely because one of the languages is a lingua franca (or simply more widespread in media), that an individual learner can more readily influence thier learning of these languages by - for instance with the help of the internet - exposing themsleves to media in the lingua franca. As a result, I feel the debate around which language should be given more support should instead be reframed as how can we empower learners to learn the lingua franca more independently so that more targeted resources can be given to smaller languages that are much harder to find for instance media in by the student.