By Angelica Wozniak

“Cherish the values and the heritage that define your identity”, a notable quote said to the Kashubian people by Pope John Paul II, a quote that deeply resonates within a culture that has been pulled away from prominence and pushed into monotony. Looking back in time, the Kashubs, a people inhabiting Northern Poland in an area near the city of Gdańsk, have both been juggled between Germany and Poland during WWII and have had their culture diluted during post-war Communist times.

During World War II, Poland was struggling to maintain its own identity and language. A whole nation was forced under submission by three different nations wanting more power and land to call their own. Polish and Kashubian were forbidden within what once was the nation of Poland. The consideration of ethnic groups was not a major concern, especially considering the fact that together with the Kashubs, minorities in Poland only constituted a total of 5% of the population during the time of the Second World War, a minimal amount. Therefore, priorities after the war were to try and regain a sense of what it meant to be Polish, with Standard Polish becoming the requirement to be a true Pole. The goal was mono-ethnicity, not cultural diversity, and “Kashubian culture…existed only as a subset of Polish folklore” (Rybińska 138). Discussing minorities was dangerous and considered a taboo, and as Poland was rising from its ashes, Kashubian was beginning to become extinguished.

Near the end of twentieth century, after WWII and Communism, Poland was becoming more modern and urbanized, and inter-generational transmission of Kashubian was on the decline, as the youth of the time were focused on attaining a more successful life. Kashubian started to die out more rapidly, with mostly older generations speaking it. Yet again, it was not considered a priority, and the culture was boiled down to the folkloric memory of farmers and fishermen. Thus, the Kashubs have been stuck in a constant battle contending for the smallest awareness of their dire situation. The Kashubs were fighting for the recognition and support of their culture, their heritage, and most importantly, their identity.

Years later, the Kashubs finally started winning this battle and became “perhaps the most powerful and most active of all Poland’s minority institutions” (Majewicz 154). Currently, there are around 500,000 speakers of Kashubian from Poland to the USA, and even in Canada.

Linguistically, Polish and Kashubian stem from the same language branch (West Slavic). However, when looking at Kashubian one can see the heavy German influence on the language. For instance, the stress on a word falls on the second to last syllable (penultimate stress) in Polish, while in Kashubian the stress tends to land on any syllable. Kashubian stress is variable, and differs between the various dialects of Kashubian. There are also a couple of differences between the Polish and Kashubian alphabets. Kashubian lacks the Polish Ą, Ę, & Ź, and instead has Ã, É, Ë, Ò, Ô & Ù. It does not distinguish (or contrast) the Polish Z, Ż, and Ź. These sounds are more similar to those in German. Kashubian also has a dual form, like Arabic, and it has more vowel contrasts than Polish does. Also, like German, Kashubian keeps its subject pronouns, whereas Polish is a pro-drop language that does not need to explicitly use its subject pronouns. (Znajkowski 23-36). For instance, the sentence ‘I’m going to the store’ can be translated in Polish as: “Ja ide do sklepu’ or in a simpler manner, ‘Ide do sklepu,’ without the first-person pronoun.

Kashubian schools have even been created, with the opening of the first Kashubian secondary school in Brusy and a primary school in Głodnica in 1991. In 2005, there were 100 Kashubian primary schools with 8000 students and growing. Other schools also allow parents to request that their children be enrolled in a course that teaches Kashubian for three hours a week. Interestingly enough, Kashubian has found its way to the university level, where students who are studying Polish philology are required to take a course on Kashubian.

In terms of power in government, the first Kashubian Congress fell apart in the 1950s. A second Kashubian Congress was thus established in June of 1992 in Gdańsk called “The Future of the Kashubs”, which organizes weekly events to help with the upkeep of the culture.

The Catholic Church has also begun to support and even promote the Kashubian language by holding services in Kashubian and translating both the New and Old Testaments of the Bible.

Kashubian has even become a protected regional language thanks to the National and Ethnic Minorities and Regional Language Act implemented by the Polish government, as well as Poland having ratified the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages in 2009.

This is without mentioning that hundreds of books have been published in Kashubian thanks to the Kashubian-Pomeranian Society, which includes handbooks that have been written about Kashubian orthography and grammar and Kashubian dictionaries that have been published as well.

Most importantly, the Kashub youth are using the language to shape their identities. They are no longer avoiding and forgetting their language and their roots. Instead, they are promoting it by making it a part of who they are; a part of their identity. There is still much work that needs to be done and much maintenance that needs to be upheld to make sure the Kashubian language stays strong. However, it is worth noting that if the Kashubs can push through years of obstacles, then they can bring their language and their culture back from the shadows of mono-ethnicity. The Kashubs will not let themselves be dissolved into folkloric myths again. This bulletproof culture will thrive and promote diversity. It will fight as valiantly as its nation once did to reclaim its spot in the world.

"Drodzy bracia i siostry Kaszubi! Strzeżcie tych wartości i tego dziedzictwa, które stanowią o Waszej tożsamości", to są znaczne słowa od papieża Jana Pawła II do Kaszubów. Ten cytat od Jana Pawła II głęboko rezonuje w Kaszubskiej kulturze, która straciła wartość i prawię zaginęła. Kaszubi, którzy mieszkają w północnej Polsce w pobliżu miasta Gdańsk, zostali rzuceni między Polską a Niemcami podczas Drugiej Wojny Światowej, jak również, podczas Komunizmu w Polsce.

Podczas Drugiej Wojny Światowej, Polska zaledwie utrzymała swoją tożsamość i bardzo starała się utrzymać swój język i swoją kulturę. Całe państwo było zmuszone do poddania się przez trzy różne narody, które chciały więcej mocy nad światem. Język Polski był zabroniony. W pewnym momencie dumny kraj, o bogatych kulturach, przestał istnieć. Kaszubska kultura nie była brana pod uwagę, szczególnie że mniejszości w Polsce osiągnęły zaledwie pięć procent populacji ludności Polski. W tym czasie, priorytetem było wzbudzenie Polskiej kultury, języka Polskiego i narodu Polskiego. Kiedy Polska powstawała ze swoich popiołów, Kaszubska kultura zaczęła zanikać.

Ponadto, po Drugiej Wojnie Światowej Polska znalazła się pod sowieckim komunizmem. Celem komunizmu było monoetniczność, a nie różnorodność kulturowa. W tym czasie, Kaszubska kultura była tylko “...podgrupą polskiego folkloru”(Rybińska 138), i niczym więcej. Rozmowa o mniejszości była tabu, a nawet przestępstwem. Kaszubska kultura szybko umierała.

Pod koniec dwudziestego wieku, po Drugiej Wojnie Światowej i po komunizmie, Polska stała się bardziej nowoczesna i miejska. To był problem Kaszubów, ponieważ młodzież Kaszubska koncentrowała się na osiągnięciu lepszego życia, a nie uczenia się o języku i kulturze Kaszubskiej. W związku z tym, międzypokoleniowa transmisja języka Kaszubskiego zmniejszała się i tylko starsze pokolenia mówiło tym językiem. Ta kultura była znana tylko dla rolników i wędkarzy. Kaszubi utknęli w nieustannej bitwie o ich uznanie i tożsamość.

Nadal istnieje nadzieja dla Kaszubów. W dzisiejszych czasach Kaszubi są jedną z “...najbardziej potężnych i najbardziej aktywnych Polskich mniejszości” (Majewicz 154). Po wielu latach, w końcu, udało się Kaszubom uratować swój język i kulturę. W obecnym czasie jest 500,000 mówców języka Kaszubskiego w Polsce, w Ameryce, i nawet w Kanadzie. Zostało otwarte wiele szkół Kaszubskich (pierwsze w Brusy i w Głodnicy w 1991 r.) w Polsce. W 2005 r. było ponad 100 szkół Kaszubskich i ponad 8000 studentów. Ta liczba wciąż rośnie. Rodzice mogą zapisać swoich dzieci aby były nauczone języka Kaszubskiego przez trzy godziny w tygodniu. Studenci które studiują Polską Filologię na Uniwersytecie Gdańskim muszą wziąć klasę o Kaszubskiej kulturze i o Kaszubskim języku.

Pomimo to że pierwszy kongres rozpadł się w 1950 r, założono drugi kongres Kaszubski który był ustalony w czerwcu 1992 r. w Gdańsku. Został nazwany “Przyszłością Kaszubów”. Ten kongres organizuje spotkania i inne wydarzenia aby awansować kulturę Kaszubską.

Nawet kościół Katolicki wspiera Kaszubów i oferuję mszy w języku Kaszubskim. Ponadto Biblia była przetłumaczona też w tym języku (Nowy Testament był wydany w 1987 r. i Stary Testament był wydany w 1992 r.)

W 2009 r. Kaszubski stał się językiem chronionym kiedy Polska ratyfikowała Europejską Kartę Języków Regionalnych i Mniejszościowych. Rząd Polski stworzył prawo Mniejszości Narodowej i Etnicznej oraz Ustawę o Językach Regionalnych żeby chronić języki które szybko gasły.

Works Cited

Dołowy-Rybińska, N. (2015). Young Kashubs and language policy. In M. Jones (Ed.), Policy and Planning for Endangered Languages: (pp. 123-137). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316162880.011

Gorter, Durk, ed. Fourth International Conference on Minority Languages: Western and Eastern European papers. Vol. 2. Multilingual matters, 1990.

Jones, Elin Haf Gruffydd, and Enrique Uribe-Jongbloed, eds. Social media and minority languages: Convergence and the creative industries. Vol. 152. Multilingual Matters, 2012.

"Kashubian Language." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Apr. 2017. Web. 23 Apr. 2017.

Majewicz, Alfred E. "Kashubian choices, Kashubian prospects: a minority language situation in northern Poland." International journal of the sociology of language 120.1 (1996): 39-54.

Majewicz, Alfred F., and Tomasz Wicherkiewicz. "Minority Rights Abuse in Communist Poland and Inherited." (1992).

Majewicz, Alfred F. "Minority situation attitudes and developments after the return to power of''post-communists''in Poland." Nationalities Papers 27.1 (1999): 115-137.

Otwinowska, Agnieszka, and Gessica De Angelis, eds. Teaching and learning in multilingual contexts: sociolinguistic and educational perspectives. Vol. 96. Multilingual Matters, 2014.

Trudgill, Peter. "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe." International Journal of Applied Linguistics 2.2 (1992): 167-177.

Znajkowski, Nick. "Language Contact in Pomerania: The Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian." Linguistics.as.nyu.edu. New York University, n.d. Web. http://linguistics.as.nyu.edu/docs/IO/29862/KashubianThesis_FINAL.pdf.

---

Angelica, a heritage speaker of Polish, was a sophomore in Speech & Hearing Sciences, Linguistics & Arabic Studies at the University of Illinois when she wrote this text in 418, 'Language and Minorities in Europe'.

|

| Source: Wikimedia Commons |

During World War II, Poland was struggling to maintain its own identity and language. A whole nation was forced under submission by three different nations wanting more power and land to call their own. Polish and Kashubian were forbidden within what once was the nation of Poland. The consideration of ethnic groups was not a major concern, especially considering the fact that together with the Kashubs, minorities in Poland only constituted a total of 5% of the population during the time of the Second World War, a minimal amount. Therefore, priorities after the war were to try and regain a sense of what it meant to be Polish, with Standard Polish becoming the requirement to be a true Pole. The goal was mono-ethnicity, not cultural diversity, and “Kashubian culture…existed only as a subset of Polish folklore” (Rybińska 138). Discussing minorities was dangerous and considered a taboo, and as Poland was rising from its ashes, Kashubian was beginning to become extinguished.

Near the end of twentieth century, after WWII and Communism, Poland was becoming more modern and urbanized, and inter-generational transmission of Kashubian was on the decline, as the youth of the time were focused on attaining a more successful life. Kashubian started to die out more rapidly, with mostly older generations speaking it. Yet again, it was not considered a priority, and the culture was boiled down to the folkloric memory of farmers and fishermen. Thus, the Kashubs have been stuck in a constant battle contending for the smallest awareness of their dire situation. The Kashubs were fighting for the recognition and support of their culture, their heritage, and most importantly, their identity.

Years later, the Kashubs finally started winning this battle and became “perhaps the most powerful and most active of all Poland’s minority institutions” (Majewicz 154). Currently, there are around 500,000 speakers of Kashubian from Poland to the USA, and even in Canada.

|

| A Kashubian dictionary. (Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

Kashubian schools have even been created, with the opening of the first Kashubian secondary school in Brusy and a primary school in Głodnica in 1991. In 2005, there were 100 Kashubian primary schools with 8000 students and growing. Other schools also allow parents to request that their children be enrolled in a course that teaches Kashubian for three hours a week. Interestingly enough, Kashubian has found its way to the university level, where students who are studying Polish philology are required to take a course on Kashubian.

In terms of power in government, the first Kashubian Congress fell apart in the 1950s. A second Kashubian Congress was thus established in June of 1992 in Gdańsk called “The Future of the Kashubs”, which organizes weekly events to help with the upkeep of the culture.

The Catholic Church has also begun to support and even promote the Kashubian language by holding services in Kashubian and translating both the New and Old Testaments of the Bible.

Kashubian has even become a protected regional language thanks to the National and Ethnic Minorities and Regional Language Act implemented by the Polish government, as well as Poland having ratified the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages in 2009.

This is without mentioning that hundreds of books have been published in Kashubian thanks to the Kashubian-Pomeranian Society, which includes handbooks that have been written about Kashubian orthography and grammar and Kashubian dictionaries that have been published as well.

Most importantly, the Kashub youth are using the language to shape their identities. They are no longer avoiding and forgetting their language and their roots. Instead, they are promoting it by making it a part of who they are; a part of their identity. There is still much work that needs to be done and much maintenance that needs to be upheld to make sure the Kashubian language stays strong. However, it is worth noting that if the Kashubs can push through years of obstacles, then they can bring their language and their culture back from the shadows of mono-ethnicity. The Kashubs will not let themselves be dissolved into folkloric myths again. This bulletproof culture will thrive and promote diversity. It will fight as valiantly as its nation once did to reclaim its spot in the world.

Kuloodporna Kultura

|

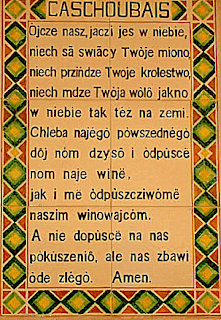

| The Lord's Prayer in Kashubian (Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

Podczas Drugiej Wojny Światowej, Polska zaledwie utrzymała swoją tożsamość i bardzo starała się utrzymać swój język i swoją kulturę. Całe państwo było zmuszone do poddania się przez trzy różne narody, które chciały więcej mocy nad światem. Język Polski był zabroniony. W pewnym momencie dumny kraj, o bogatych kulturach, przestał istnieć. Kaszubska kultura nie była brana pod uwagę, szczególnie że mniejszości w Polsce osiągnęły zaledwie pięć procent populacji ludności Polski. W tym czasie, priorytetem było wzbudzenie Polskiej kultury, języka Polskiego i narodu Polskiego. Kiedy Polska powstawała ze swoich popiołów, Kaszubska kultura zaczęła zanikać.

Ponadto, po Drugiej Wojnie Światowej Polska znalazła się pod sowieckim komunizmem. Celem komunizmu było monoetniczność, a nie różnorodność kulturowa. W tym czasie, Kaszubska kultura była tylko “...podgrupą polskiego folkloru”(Rybińska 138), i niczym więcej. Rozmowa o mniejszości była tabu, a nawet przestępstwem. Kaszubska kultura szybko umierała.

Pod koniec dwudziestego wieku, po Drugiej Wojnie Światowej i po komunizmie, Polska stała się bardziej nowoczesna i miejska. To był problem Kaszubów, ponieważ młodzież Kaszubska koncentrowała się na osiągnięciu lepszego życia, a nie uczenia się o języku i kulturze Kaszubskiej. W związku z tym, międzypokoleniowa transmisja języka Kaszubskiego zmniejszała się i tylko starsze pokolenia mówiło tym językiem. Ta kultura była znana tylko dla rolników i wędkarzy. Kaszubi utknęli w nieustannej bitwie o ich uznanie i tożsamość.

Nadal istnieje nadzieja dla Kaszubów. W dzisiejszych czasach Kaszubi są jedną z “...najbardziej potężnych i najbardziej aktywnych Polskich mniejszości” (Majewicz 154). Po wielu latach, w końcu, udało się Kaszubom uratować swój język i kulturę. W obecnym czasie jest 500,000 mówców języka Kaszubskiego w Polsce, w Ameryce, i nawet w Kanadzie. Zostało otwarte wiele szkół Kaszubskich (pierwsze w Brusy i w Głodnicy w 1991 r.) w Polsce. W 2005 r. było ponad 100 szkół Kaszubskich i ponad 8000 studentów. Ta liczba wciąż rośnie. Rodzice mogą zapisać swoich dzieci aby były nauczone języka Kaszubskiego przez trzy godziny w tygodniu. Studenci które studiują Polską Filologię na Uniwersytecie Gdańskim muszą wziąć klasę o Kaszubskiej kulturze i o Kaszubskim języku.

Pomimo to że pierwszy kongres rozpadł się w 1950 r, założono drugi kongres Kaszubski który był ustalony w czerwcu 1992 r. w Gdańsku. Został nazwany “Przyszłością Kaszubów”. Ten kongres organizuje spotkania i inne wydarzenia aby awansować kulturę Kaszubską.

Nawet kościół Katolicki wspiera Kaszubów i oferuję mszy w języku Kaszubskim. Ponadto Biblia była przetłumaczona też w tym języku (Nowy Testament był wydany w 1987 r. i Stary Testament był wydany w 1992 r.)

W 2009 r. Kaszubski stał się językiem chronionym kiedy Polska ratyfikowała Europejską Kartę Języków Regionalnych i Mniejszościowych. Rząd Polski stworzył prawo Mniejszości Narodowej i Etnicznej oraz Ustawę o Językach Regionalnych żeby chronić języki które szybko gasły.

Works Cited

Dołowy-Rybińska, N. (2015). Young Kashubs and language policy. In M. Jones (Ed.), Policy and Planning for Endangered Languages: (pp. 123-137). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316162880.011

Gorter, Durk, ed. Fourth International Conference on Minority Languages: Western and Eastern European papers. Vol. 2. Multilingual matters, 1990.

Jones, Elin Haf Gruffydd, and Enrique Uribe-Jongbloed, eds. Social media and minority languages: Convergence and the creative industries. Vol. 152. Multilingual Matters, 2012.

"Kashubian Language." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Apr. 2017. Web. 23 Apr. 2017.

Majewicz, Alfred E. "Kashubian choices, Kashubian prospects: a minority language situation in northern Poland." International journal of the sociology of language 120.1 (1996): 39-54.

Majewicz, Alfred F., and Tomasz Wicherkiewicz. "Minority Rights Abuse in Communist Poland and Inherited." (1992).

Majewicz, Alfred F. "Minority situation attitudes and developments after the return to power of''post-communists''in Poland." Nationalities Papers 27.1 (1999): 115-137.

Otwinowska, Agnieszka, and Gessica De Angelis, eds. Teaching and learning in multilingual contexts: sociolinguistic and educational perspectives. Vol. 96. Multilingual Matters, 2014.

Trudgill, Peter. "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe." International Journal of Applied Linguistics 2.2 (1992): 167-177.

Znajkowski, Nick. "Language Contact in Pomerania: The Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian." Linguistics.as.nyu.edu. New York University, n.d. Web. http://linguistics.as.nyu.edu/docs/IO/29862/KashubianThesis_FINAL.pdf.

---

Angelica, a heritage speaker of Polish, was a sophomore in Speech & Hearing Sciences, Linguistics & Arabic Studies at the University of Illinois when she wrote this text in 418, 'Language and Minorities in Europe'.

Comments

Post a Comment

The moderators of the Linguis Europae blog reserve the right to delete any comments that they deem inappropriate. This may include, but is not limited to, spam, racist or disrespectful comments about other cultures/groups or directed at other commenters, and explicit language.