Between the State and the Charter: The Precarious and Dangerous Situation of the Co-Official, Regional, and Immigrant Languages in Spain

By Nick Ortiz

It has been twenty-seven years since the writing of the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages (ECRML) and eighteen years since its ratification in Spain. Since then, the Spanish government has cultivated its own image: one of a country that guarantees the protection of regional languages required by the Statutes of Autonomy in the Spanish Constitution and by the ECRML. However, this image can be deceiving. Every language, even the co-official ones, remain suppressed and marginalized to various degrees in Spain due to the neglect and the weakness shown by the Charter and the central government in Madrid. There are numerous marginalized languages that span across almost every region of Spain: Leonese in Castile-Leon, Asturian and Galician-Asturian in Asturias, Portuguese and Galician in Extremadura, Valencian in Murcia, Aragonese in Aragon, Dariya in Ceuta, Tamazight/Amazige (a variety of Berber) in Melilla, and Polish and Romanian in the largest urban centers such as Madrid and Barcelona. If one compares the protection of these languages to those that enjoy a co-official status or a higher level of recognition (like that of Catalan, Galician, Basque, Valencian and Aranese), their protection leaves much to be desired.

Up until now the language situation regarding Catalan, Galician, Basque, Valencian, and Aranese has definitely improved due to support from the ECRML, the Statutes of Autonomy, and regional policies. However, the protection and preservation of these languages have experienced their own obstacles with respect to their scope and implementation. Since the promulgation of the Statutes of Autonomy in 1978, the use of Catalan, Galician, Basque, Valencian, and Aranese has spread in their own regions as co-official languages: Catalan in Catalonia and the Balearic Islands, Galician in Galicia, Basque in the Basque Country, Valencian in Valencia, and Aranese in the Aran Valley (Catalonia). The ECRML has played a key role in this process through a procedure in which it oversees the Spanish government. The main European institutions responsible for this monitoring are the Committee of Experts and the Council of Ministers that direct the process in the name of the Council of Europe. The pressure exerted by the Committee of Experts and the Council of Ministers has produced suggestions and recommendations (that combined with the regional policies) has pushed the Spanish government into action with respect to language policies. There are now more primary and secondary schools that teach exclusively in the co-official languages and the languages themselves have been given an elevated status in politics and administration.

These noteworthy successes have hidden the structural problems that still threaten the further spread of the co-official languages. According to the reports of the Committee of Ministers, the use of co-official languages continues to be limited in social domains especially in provinces (such as the Balearic Islands and Valencia) where a trilingual model has been introduced to encourage the teaching of English. This system threatens the teaching of Catalan and Valencian at a time where there still exists a dearth of bureaucrats, judges, lawyers, and officials that do not know the co-official languages. The number of translations relating to legal, national, and public policies in co-official languages has not kept up with the demand. On top of that, the majority of media in Spain continues to be transmitted in Castilian despite the quotas that have been put in place in favor of co-official languages. The languages concerned are protected but they are not privileged. According to experts, such as F. Xavier Vila i Moreno, the Spanish government has taken a position that favors and protects the privileged status of Castilian in the media, public administrations, and businesses. It gives only a limited autonomy to regions within a centralized structure that reduces the chances of co-official languages of escaping from their subordinated position (Vila i Moreno, 157-179).

If the situation of the regional languages is bad, the situation of the other languages that do not enjoy the same status is even worse. According to various sociolinguistic surveys and the 2011 census, there are 250,000 Asturian speakers (1/4 of the regional population) in Asturias, 54,481 Aragonese speakers in Aragon, and 50,000 Galician speakers in Castile-Leon. Despite the protests of the Committee of Experts, Asturian officials to this day have not recognized Asturian as a co-official language and their Aragonese and Leonese counterparts have not taken the necessary steps to increase the use of Catalan, Aragonese, and Galician outside private domains. Compared with languages that have more attention and more protection because of their co-official status, the presence of these languages in primary schools is poor in comparison. There are no available statistics regarding the presence of Leonese, Galician-Asturian, and Portuguese, but these languages also suffer from the same neglect.

One can see a worser situation in the case of Tamazight/Amazige, Dariya, Polish, and Romanian. Regarding Amazige, estimates on the number of speakers in Melilla range from 20,000-35,000 (40% of the city’s population) according to studies done by local institutions. The presence of Amazige in Melilla is similar to that of Dariya in Ceuta. According to the recent census, estimates on the number of Dariya speakers range from 40.5%-45% of the total population. This means that there are around 30,000-36,000 Dariya speakers in Ceuta. Despite the large presence of these two languages that are spoken by a quarter of the population of Melilla and Ceuta, Amazige and Dariya do not have the recognition and respect they deserve. Regardless of the big step that was taken in 2013 where local officials in Melilla passed the Intercultural Social Pact that gave a level of protection to Amazige as a traditional language in Melilla’s heritage, Amazige’s future in the city is still far from secure. The population of Polish and Romanian speakers is currently greater than that of Amazige and Dariya. According to experts such as Ruth Ferrero Turrión, in 2008 migrants from Eastern Europe composed 25% of the foreign population in Spain. From this group, 664,880 are Romanian and 76,050 are Polish (Ferrero Turrión, 58).

Despite their tremendous demographic presence, the aforementioned languages suffer from the weaknesses of not only the Spanish state but also the ECRML itself. The ECRML only recognizes languages that are “protégées traditionnellement sur un territoire d’un État.” This definition implies the exclusion of dialects of the official language and migrant languages. This territorial definition has been used to claim protection for Amazige and Dariya with mixed results by the Committee of Experts. However, in spite of their large presence in Spain, this same definition under the ECRML has completely abandoned Polish and Romanian since they are considered to be migrant languages. It seems apparent that both the ECRML and the Spanish central government to varying degrees ignore or devalue languages that do not fit their standards of what constitutes Western European culture, co-official status, or Spain’s heritage.

It must be said that the Spanish government uses the territorial bias of the ECRML as a strategy to prevent the addition of more co-official languages and to withhold recognition and preservation of several languages that deserve the same protection as the established co-official ones. The Committee of Experts can pressure the Spanish government, but the scope of this pressure is very limited. A good example is the Social Pact that has changed the current status of Amazige to a certain extent in Melilla. This episode is reminiscent of the arguments put forward by experts such as Vila i Moreno. The Pact seems to be a local initiative in conjunction with European pressure that plays a role despite the limited territorial definition of the ECRML. When a language fits the definition of a minority language under the ECRML, the Charter itself becomes a tool to pressure authorities as in the case of Amazige. While this pressure has favored Amazige, it has been ineffective towards Dariya even though the language complies with the same territorial definition of the ECRML. The governments of Spain and Ceuta have done almost nothing for Dariya. Nowadays they continue the resist the demands of European ministers to recognize it as a territorial language even when almost half the city’s population speaks it. They also continue to ignore Polish and Romanian whose number has continued to grow every year in terms of speakers due to the increased rate of integration between the member states of the European Union.

This systematic lack of recognition (that seems to be on purpose) towards languages in Spain is part of a larger process where the Spanish government protects the dominant and privileged status of Castilian. This protection is connected to the maintenance of Spain’s image as a country that respects the linguistic diversity valued by the ECRML. It has been noted that regional initiatives and pressure from European institutions are the main factors behind the preservation of regional languages in Spain. The priorities of the Spanish government since 1978 have been to maintain Castilian as the dominant language, grant limited concessions of autonomy to co-official languages, and to withhold protection from languages considered to be non-Western, outside Spain’s heritage, and spoken by migrants. This strategy has helped to preserve the dominance of Castilian while at the same time reinforcing this image of linguistic diversity and tolerance. This is Spain’s linguistic reality. As long as the Spanish government does not consider the spread of all languages in its borders as a priority, the ECRML maintains its strict, territorial definition of what constitutes a regional or minority language, and nothing radical happens within Spain or in the European Union, this precarious situation will continue to threaten the future of not only the co-official languages but all languages that compose Spain’s linguistic landscape.

Había sido veinte y siete años desde la escritura de la Carta Europea de las Lenguas Regionales y Minoritarias (CELRM) y dieciocho años desde su ratificación en España. Desde entonces, el gobierno español ha cultivado su propia imagen: la de un país que garantiza la protección de los idiomas regionales mandada por los Estatutos de Autonomía en la Constitución Española y por la CELRM. No obstante, esta imagen es decepcionante. Todos los idiomas, aún los idiomas cooficiales, se quedan suprimidos y marginados en varios grados en España a causa del descuido y de la debilidad exhibidos por la Carta y el régimen español. El número de lenguas marginadas es numeroso y abarca casi todas las regiones de España: el leonés en Castilla y León, el asturiano y el gallego-asturiano en Asturias, el portugués y el gallego en Extremadura, el valenciano en Murcia, el aragonés en Aragon, el dariya/árabe ceutí en Ceuta, el tamazight/amazige (un tipo de beréber) en Melilla y el polonés y el rumano en los mayores centros urbanos como Madrid y Barcelona. La protección de eses idiomas faltan mucho en comparación con aquellos que tienen un estatus cooficial o un grado más alto de reconocimiento como el catalan, el gallego, el vasco, el valenciano y el aranés.

De verdad, hasta entonces la situación lingüística del catalan, gallego, vasco, valenciano y aranés ha mejorado a causa del apoyo de la CELRM, los Estatutos de Autonomía y las políticas regionales pero la protección y salvaguarda de aquellos idiomas tienen sus propios tropiezos con respeto a su alcance y aplicación. Desde la promulgación des los Estatutos de Autonomía en 1978, el uso del catalan, el gallego, el vasco, el valenciano y el aranés ha ampliado en sus propios regiones como lenguas co-oficiales: el catalan en Cataluña y las Islas Baleares, el gallego en Galicia, el vasco en el País Vasco, el valenciano en Valencia y el aranés en el Valle de Arán (Cataluña). La CELRM ha jugado un rol clave en este proceso por medio del procedimiento en lo que supervisar el gobierno español. Las instituciones europeas principales que son responsables por la supervisión son el Comité de Expertos y el Consejo de los Ministros que encabezan el proceso en nombre del Consejo de Europa. La presión del Comité de Expertos y del Consejo de los Ministros ha producido sugerencias y recomendaciones que en conjunción con las políticas regionales ha impulsado el gobierno español a la acción con respeto a las políticas lingüísticas. Hay más escuelas primarias y secundarias que enseñan exclusivamente en los idiomas cooficiales y los idiomas se han sido concedido un mayor estatus político y administrativo.

Estes éxitos notables han escondido los problemas estructurales que todavía amenazan la continua ampliación de los idiomas cooficiales. Según los informes del Comité de Expertos, el uso de los idiomas cooficiales sigue ser restringido en la esfera social especialmente en provincias (como las Islas Baleares y Valencia) donde un modelo trilingüe ha sido introducido para fomentar la enseñanza de inglés. Este sistema pone en peligro la enseñanza del catalán y del valenciano al momento que todavía existe una gran falta de funcionarios público, jueces, abogados y agentes que no conocen los idiomas cooficiales. El número de translaciones de leyes y de políticas nacionales y públicas en idiomas cooficiales ha fallado seguir el ritmo con la demanda. Además, la mayoría de las medias en España sigue ser transmitido en castellano a pesar de la imposición de cuotas a favor de las lenguas cooficiales. Los idiomas en cuestión son protegidos pero no son privilegiados. Según expertos, como F. Xavier Vila i Moreno, el gobierno español ha adoptado una posición que favorece y protege el estatus privilegiado del castellano a través del país en las medias, la administraciones públicas y las empresas. Ello solamente concede una autonomía limitada a las regiones en una estructura centralista que perjudica las chances de las lenguas cooficiales de escapar de su posición subordinada (Vila i Moreno, 157-179).

Si la situación de los idiomas cooficiales es lamentable, la situación de los otros idiomas que no disfrutan del mismo estatus es pésima. Según varios encuestas sociolingüísticas y el censo de 2011, hay 250,000 hablantes de asturiano (un cuarto de la población regional) en Asturias, 54,481 hablantes de aragonés en Aragón y 50,000 hablantes de gallego en Castilla y León. A pesar de las protestas del Comité de Expertos, los gobernantes de Asturias no han hasta la fecha reconocido el asturiano como lengua cooficial y sus contrapartes aragoneses y leoneses no han tomado los pasos necesarios de ampliar el uso del aragonés y del gallego fuera de la esfera privada. La presencia de aquellos idiomas en las escuelas primarias es pobre en comparación con los idiomas que disfrutan de más atención y de más protección a causa de su estatus como lengua cooficial. No hay estadísticos definitivos sobre la presencia del leonés, del gallego-asturiano y del portugués pero aquellos también sufren del mismo descuido.

La situación es peor por el tamzight/amazige, el dariya/árabe ceutí, el polaco y el rumano. Con respeto al amazige, las aproximaciones sobre el número de hablantes en Melilla son entre 20,000-35,000 (40% de la población urbana) según estudios mandados por instituciones locales. La presencia de amazige en Meilla hace eco con la de dariya. Según el censo más reciente, las aproximaciones del número de hablantes de dariya tiene alcance de 40.5% al 45% de la población total. Esto significa que hay cerca de 30,000-36,000 hablantes de dariya en Ceuta. A pesar de la larga presencia de los dos idiomas que son hablados por un cuarto de la población melillenses y ceutís, el amazige y el dariya no tiene el reconocimiento y el respeto que merecen. A pesar del gran paso que ocurrió en 2013 donde las autoridades melillenses han promulgado el Pacto Social por la Interculturalidad que concediera un grado de protección al amazige como lengua tradicional del patrimonio melillense, resta mucho para preservar el porvenir de amazige en la ciudad. La población que habla el polaco y el rumano es mayor que la que habla el amazige y el dariya. Según expertos como Ruth Ferrero Turrión, en 2008 migrantes del este de Europa se comprenden 25% de la población extranjera en España. De esa población, 664,880 son rumanos y 76,050 son polacos (Ferrero Turrión, 58).

A pesar de su tremendo presencia demográfica, los idiomas susodichos sufren de los defectos de no solamente del estado español sino la CELRM por sí. La CELRM solo reconoce lenguas que son “pratiquées traditionnellement sur un territoire d’un État” que no incluye los dialectos del idioma oficial ni los idiomas de migrantes. Esta definición territorial se ha sido reclamada para el amazige y el dariya con éxitos mixtos por el Comité de Expertos pero esta definición limitada ha completamente abandonado los idiomas que son considerados lenguas de migrantes aunque posean más hablantes entre la población española. Nos parece que los idiomas que no representan la cultura occidental europea, disfrutan de un estatus cooficial o no se reconocen como parte del patrimonio de España son ignorados o menospreciados como idiomas inmigrantes.

Hay que percibir que el gobierno español usa, como estratagema, la predisposición territorial de la CELRM para impedir la añadidura de más idiomas cooficiales y para denegar el reconocimiento y salvaguarda de varios idiomas que merecen la misma protección que los idiomas cooficiales establecidos. El Comité de Expertos se puede presionar al gobierno español pero esa presión es limitada. Un buen ejemplo es el Pacto Social que ha cambiado hasta cierto punto el estado actual del amazige en Melilla. Este episodio hace eco con el argumento de expertos como Vila i Moreno. El Pacto parece ser una iniciativa local con la presión europea jugando un rol a pesar de la definición limitada territorial de la CELRM. Cuando un idioma conforme con las condiciones estipuladas, la CELRM se hace un instrumento de presión con respeto al amazige. Mientras que esta presión favoreció el amazige, ha sido ineficaz con respeto al dariya aún cuando este idioma conforme con la definición territorial de la CELRM. El gobierno nacional y ceutí han hecho casi nada por el dariya. Hoy en día ellos siguen resistir las demandas de los ministros europeos de reconocerlo como idioma territorial aunque haya casi una mitad de la población citadina de Ceuta lo habla. Ellos también continúan ignorar los idiomas polacos y rumanos cuyos número de hablantes crece cada año a causa del alto grado de integración entre los estados miembros de la Unión Europea.

Esta falta sistemática de reconocimiento (prácticamente a propósito) de idiomas en España hace parte de un proceso más largo al parte del gobierno español de proteger el estatus dominante y privilegiado de castellano. Esta protección se enlaza con el mantenimiento de la imagen de España como país que respeta la diversidad lingüística valorada por la CELRM. Hemos visto que las incitativas regionales y la presión europea son los factores principales en la salvaguarda de los idiomas regionales en España. Las prioridades del gobierno español, desde 1978, son de mantener el castellano como lengua dominante, de echar concesiones limitadas a los idiomas cooficiales y de retener la protección de idiomas considerados inmigrantes, no occidentales, o no patrimoniales mientras preservando esta imagen de diversidad lingüística y de tolerancia. Así es la actualidad lingüística de España. Mientras que el gobierno no considere la ampliación de todos los idiomas como prioridad, la CELRM mantenga una definición estricta y territorial de lo que constituye un idioma regional y no pase algo radical en el entorno español o europeo, la situación, de no solamente los idiomas cooficiales pero todos los idiomas que hacen parte del paisaje lingüístico español, seguirá siendo precaria y peligrosa por todas las lenguas en cuestión.

Nick Ortiz is a graduate student in History at The University of Illinois. Nick’s future plans include finishing his research. Nick wrote this blog post in the 418 ‘Language and Minorities in Europe’ course in spring 2019.

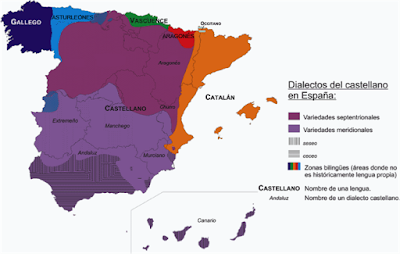

|

| Source: Wikimedia Commons |

Up until now the language situation regarding Catalan, Galician, Basque, Valencian, and Aranese has definitely improved due to support from the ECRML, the Statutes of Autonomy, and regional policies. However, the protection and preservation of these languages have experienced their own obstacles with respect to their scope and implementation. Since the promulgation of the Statutes of Autonomy in 1978, the use of Catalan, Galician, Basque, Valencian, and Aranese has spread in their own regions as co-official languages: Catalan in Catalonia and the Balearic Islands, Galician in Galicia, Basque in the Basque Country, Valencian in Valencia, and Aranese in the Aran Valley (Catalonia). The ECRML has played a key role in this process through a procedure in which it oversees the Spanish government. The main European institutions responsible for this monitoring are the Committee of Experts and the Council of Ministers that direct the process in the name of the Council of Europe. The pressure exerted by the Committee of Experts and the Council of Ministers has produced suggestions and recommendations (that combined with the regional policies) has pushed the Spanish government into action with respect to language policies. There are now more primary and secondary schools that teach exclusively in the co-official languages and the languages themselves have been given an elevated status in politics and administration.

These noteworthy successes have hidden the structural problems that still threaten the further spread of the co-official languages. According to the reports of the Committee of Ministers, the use of co-official languages continues to be limited in social domains especially in provinces (such as the Balearic Islands and Valencia) where a trilingual model has been introduced to encourage the teaching of English. This system threatens the teaching of Catalan and Valencian at a time where there still exists a dearth of bureaucrats, judges, lawyers, and officials that do not know the co-official languages. The number of translations relating to legal, national, and public policies in co-official languages has not kept up with the demand. On top of that, the majority of media in Spain continues to be transmitted in Castilian despite the quotas that have been put in place in favor of co-official languages. The languages concerned are protected but they are not privileged. According to experts, such as F. Xavier Vila i Moreno, the Spanish government has taken a position that favors and protects the privileged status of Castilian in the media, public administrations, and businesses. It gives only a limited autonomy to regions within a centralized structure that reduces the chances of co-official languages of escaping from their subordinated position (Vila i Moreno, 157-179).

If the situation of the regional languages is bad, the situation of the other languages that do not enjoy the same status is even worse. According to various sociolinguistic surveys and the 2011 census, there are 250,000 Asturian speakers (1/4 of the regional population) in Asturias, 54,481 Aragonese speakers in Aragon, and 50,000 Galician speakers in Castile-Leon. Despite the protests of the Committee of Experts, Asturian officials to this day have not recognized Asturian as a co-official language and their Aragonese and Leonese counterparts have not taken the necessary steps to increase the use of Catalan, Aragonese, and Galician outside private domains. Compared with languages that have more attention and more protection because of their co-official status, the presence of these languages in primary schools is poor in comparison. There are no available statistics regarding the presence of Leonese, Galician-Asturian, and Portuguese, but these languages also suffer from the same neglect.

One can see a worser situation in the case of Tamazight/Amazige, Dariya, Polish, and Romanian. Regarding Amazige, estimates on the number of speakers in Melilla range from 20,000-35,000 (40% of the city’s population) according to studies done by local institutions. The presence of Amazige in Melilla is similar to that of Dariya in Ceuta. According to the recent census, estimates on the number of Dariya speakers range from 40.5%-45% of the total population. This means that there are around 30,000-36,000 Dariya speakers in Ceuta. Despite the large presence of these two languages that are spoken by a quarter of the population of Melilla and Ceuta, Amazige and Dariya do not have the recognition and respect they deserve. Regardless of the big step that was taken in 2013 where local officials in Melilla passed the Intercultural Social Pact that gave a level of protection to Amazige as a traditional language in Melilla’s heritage, Amazige’s future in the city is still far from secure. The population of Polish and Romanian speakers is currently greater than that of Amazige and Dariya. According to experts such as Ruth Ferrero Turrión, in 2008 migrants from Eastern Europe composed 25% of the foreign population in Spain. From this group, 664,880 are Romanian and 76,050 are Polish (Ferrero Turrión, 58).

Despite their tremendous demographic presence, the aforementioned languages suffer from the weaknesses of not only the Spanish state but also the ECRML itself. The ECRML only recognizes languages that are “protégées traditionnellement sur un territoire d’un État.” This definition implies the exclusion of dialects of the official language and migrant languages. This territorial definition has been used to claim protection for Amazige and Dariya with mixed results by the Committee of Experts. However, in spite of their large presence in Spain, this same definition under the ECRML has completely abandoned Polish and Romanian since they are considered to be migrant languages. It seems apparent that both the ECRML and the Spanish central government to varying degrees ignore or devalue languages that do not fit their standards of what constitutes Western European culture, co-official status, or Spain’s heritage.

It must be said that the Spanish government uses the territorial bias of the ECRML as a strategy to prevent the addition of more co-official languages and to withhold recognition and preservation of several languages that deserve the same protection as the established co-official ones. The Committee of Experts can pressure the Spanish government, but the scope of this pressure is very limited. A good example is the Social Pact that has changed the current status of Amazige to a certain extent in Melilla. This episode is reminiscent of the arguments put forward by experts such as Vila i Moreno. The Pact seems to be a local initiative in conjunction with European pressure that plays a role despite the limited territorial definition of the ECRML. When a language fits the definition of a minority language under the ECRML, the Charter itself becomes a tool to pressure authorities as in the case of Amazige. While this pressure has favored Amazige, it has been ineffective towards Dariya even though the language complies with the same territorial definition of the ECRML. The governments of Spain and Ceuta have done almost nothing for Dariya. Nowadays they continue the resist the demands of European ministers to recognize it as a territorial language even when almost half the city’s population speaks it. They also continue to ignore Polish and Romanian whose number has continued to grow every year in terms of speakers due to the increased rate of integration between the member states of the European Union.

This systematic lack of recognition (that seems to be on purpose) towards languages in Spain is part of a larger process where the Spanish government protects the dominant and privileged status of Castilian. This protection is connected to the maintenance of Spain’s image as a country that respects the linguistic diversity valued by the ECRML. It has been noted that regional initiatives and pressure from European institutions are the main factors behind the preservation of regional languages in Spain. The priorities of the Spanish government since 1978 have been to maintain Castilian as the dominant language, grant limited concessions of autonomy to co-official languages, and to withhold protection from languages considered to be non-Western, outside Spain’s heritage, and spoken by migrants. This strategy has helped to preserve the dominance of Castilian while at the same time reinforcing this image of linguistic diversity and tolerance. This is Spain’s linguistic reality. As long as the Spanish government does not consider the spread of all languages in its borders as a priority, the ECRML maintains its strict, territorial definition of what constitutes a regional or minority language, and nothing radical happens within Spain or in the European Union, this precarious situation will continue to threaten the future of not only the co-official languages but all languages that compose Spain’s linguistic landscape.

Entre el Estado y la Carta: La Situación Precaria y Peligrosa de los Idiomas Cooficiales, Regionales y Inmigrantes de España

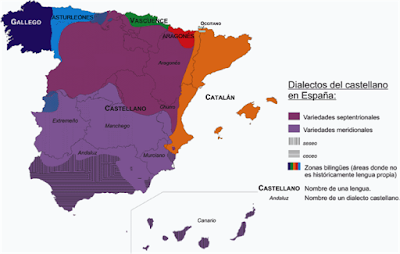

|

| La fuente de esta foto: Wikimedia Commons |

De verdad, hasta entonces la situación lingüística del catalan, gallego, vasco, valenciano y aranés ha mejorado a causa del apoyo de la CELRM, los Estatutos de Autonomía y las políticas regionales pero la protección y salvaguarda de aquellos idiomas tienen sus propios tropiezos con respeto a su alcance y aplicación. Desde la promulgación des los Estatutos de Autonomía en 1978, el uso del catalan, el gallego, el vasco, el valenciano y el aranés ha ampliado en sus propios regiones como lenguas co-oficiales: el catalan en Cataluña y las Islas Baleares, el gallego en Galicia, el vasco en el País Vasco, el valenciano en Valencia y el aranés en el Valle de Arán (Cataluña). La CELRM ha jugado un rol clave en este proceso por medio del procedimiento en lo que supervisar el gobierno español. Las instituciones europeas principales que son responsables por la supervisión son el Comité de Expertos y el Consejo de los Ministros que encabezan el proceso en nombre del Consejo de Europa. La presión del Comité de Expertos y del Consejo de los Ministros ha producido sugerencias y recomendaciones que en conjunción con las políticas regionales ha impulsado el gobierno español a la acción con respeto a las políticas lingüísticas. Hay más escuelas primarias y secundarias que enseñan exclusivamente en los idiomas cooficiales y los idiomas se han sido concedido un mayor estatus político y administrativo.

Estes éxitos notables han escondido los problemas estructurales que todavía amenazan la continua ampliación de los idiomas cooficiales. Según los informes del Comité de Expertos, el uso de los idiomas cooficiales sigue ser restringido en la esfera social especialmente en provincias (como las Islas Baleares y Valencia) donde un modelo trilingüe ha sido introducido para fomentar la enseñanza de inglés. Este sistema pone en peligro la enseñanza del catalán y del valenciano al momento que todavía existe una gran falta de funcionarios público, jueces, abogados y agentes que no conocen los idiomas cooficiales. El número de translaciones de leyes y de políticas nacionales y públicas en idiomas cooficiales ha fallado seguir el ritmo con la demanda. Además, la mayoría de las medias en España sigue ser transmitido en castellano a pesar de la imposición de cuotas a favor de las lenguas cooficiales. Los idiomas en cuestión son protegidos pero no son privilegiados. Según expertos, como F. Xavier Vila i Moreno, el gobierno español ha adoptado una posición que favorece y protege el estatus privilegiado del castellano a través del país en las medias, la administraciones públicas y las empresas. Ello solamente concede una autonomía limitada a las regiones en una estructura centralista que perjudica las chances de las lenguas cooficiales de escapar de su posición subordinada (Vila i Moreno, 157-179).

Si la situación de los idiomas cooficiales es lamentable, la situación de los otros idiomas que no disfrutan del mismo estatus es pésima. Según varios encuestas sociolingüísticas y el censo de 2011, hay 250,000 hablantes de asturiano (un cuarto de la población regional) en Asturias, 54,481 hablantes de aragonés en Aragón y 50,000 hablantes de gallego en Castilla y León. A pesar de las protestas del Comité de Expertos, los gobernantes de Asturias no han hasta la fecha reconocido el asturiano como lengua cooficial y sus contrapartes aragoneses y leoneses no han tomado los pasos necesarios de ampliar el uso del aragonés y del gallego fuera de la esfera privada. La presencia de aquellos idiomas en las escuelas primarias es pobre en comparación con los idiomas que disfrutan de más atención y de más protección a causa de su estatus como lengua cooficial. No hay estadísticos definitivos sobre la presencia del leonés, del gallego-asturiano y del portugués pero aquellos también sufren del mismo descuido.

La situación es peor por el tamzight/amazige, el dariya/árabe ceutí, el polaco y el rumano. Con respeto al amazige, las aproximaciones sobre el número de hablantes en Melilla son entre 20,000-35,000 (40% de la población urbana) según estudios mandados por instituciones locales. La presencia de amazige en Meilla hace eco con la de dariya. Según el censo más reciente, las aproximaciones del número de hablantes de dariya tiene alcance de 40.5% al 45% de la población total. Esto significa que hay cerca de 30,000-36,000 hablantes de dariya en Ceuta. A pesar de la larga presencia de los dos idiomas que son hablados por un cuarto de la población melillenses y ceutís, el amazige y el dariya no tiene el reconocimiento y el respeto que merecen. A pesar del gran paso que ocurrió en 2013 donde las autoridades melillenses han promulgado el Pacto Social por la Interculturalidad que concediera un grado de protección al amazige como lengua tradicional del patrimonio melillense, resta mucho para preservar el porvenir de amazige en la ciudad. La población que habla el polaco y el rumano es mayor que la que habla el amazige y el dariya. Según expertos como Ruth Ferrero Turrión, en 2008 migrantes del este de Europa se comprenden 25% de la población extranjera en España. De esa población, 664,880 son rumanos y 76,050 son polacos (Ferrero Turrión, 58).

A pesar de su tremendo presencia demográfica, los idiomas susodichos sufren de los defectos de no solamente del estado español sino la CELRM por sí. La CELRM solo reconoce lenguas que son “pratiquées traditionnellement sur un territoire d’un État” que no incluye los dialectos del idioma oficial ni los idiomas de migrantes. Esta definición territorial se ha sido reclamada para el amazige y el dariya con éxitos mixtos por el Comité de Expertos pero esta definición limitada ha completamente abandonado los idiomas que son considerados lenguas de migrantes aunque posean más hablantes entre la población española. Nos parece que los idiomas que no representan la cultura occidental europea, disfrutan de un estatus cooficial o no se reconocen como parte del patrimonio de España son ignorados o menospreciados como idiomas inmigrantes.

Hay que percibir que el gobierno español usa, como estratagema, la predisposición territorial de la CELRM para impedir la añadidura de más idiomas cooficiales y para denegar el reconocimiento y salvaguarda de varios idiomas que merecen la misma protección que los idiomas cooficiales establecidos. El Comité de Expertos se puede presionar al gobierno español pero esa presión es limitada. Un buen ejemplo es el Pacto Social que ha cambiado hasta cierto punto el estado actual del amazige en Melilla. Este episodio hace eco con el argumento de expertos como Vila i Moreno. El Pacto parece ser una iniciativa local con la presión europea jugando un rol a pesar de la definición limitada territorial de la CELRM. Cuando un idioma conforme con las condiciones estipuladas, la CELRM se hace un instrumento de presión con respeto al amazige. Mientras que esta presión favoreció el amazige, ha sido ineficaz con respeto al dariya aún cuando este idioma conforme con la definición territorial de la CELRM. El gobierno nacional y ceutí han hecho casi nada por el dariya. Hoy en día ellos siguen resistir las demandas de los ministros europeos de reconocerlo como idioma territorial aunque haya casi una mitad de la población citadina de Ceuta lo habla. Ellos también continúan ignorar los idiomas polacos y rumanos cuyos número de hablantes crece cada año a causa del alto grado de integración entre los estados miembros de la Unión Europea.

Esta falta sistemática de reconocimiento (prácticamente a propósito) de idiomas en España hace parte de un proceso más largo al parte del gobierno español de proteger el estatus dominante y privilegiado de castellano. Esta protección se enlaza con el mantenimiento de la imagen de España como país que respeta la diversidad lingüística valorada por la CELRM. Hemos visto que las incitativas regionales y la presión europea son los factores principales en la salvaguarda de los idiomas regionales en España. Las prioridades del gobierno español, desde 1978, son de mantener el castellano como lengua dominante, de echar concesiones limitadas a los idiomas cooficiales y de retener la protección de idiomas considerados inmigrantes, no occidentales, o no patrimoniales mientras preservando esta imagen de diversidad lingüística y de tolerancia. Así es la actualidad lingüística de España. Mientras que el gobierno no considere la ampliación de todos los idiomas como prioridad, la CELRM mantenga una definición estricta y territorial de lo que constituye un idioma regional y no pase algo radical en el entorno español o europeo, la situación, de no solamente los idiomas cooficiales pero todos los idiomas que hacen parte del paisaje lingüístico español, seguirá siendo precaria y peligrosa por todas las lenguas en cuestión.

Thank you for sharing this! It helped me to see how things look on paper does not always reflect reality. Especially from an outsider's perspective, I feel like it is important to learn.

ReplyDelete