by Emily Sardarov

Emily Sardarov wrote this blog post as a senior in Linguistics in 418 'Language and Minorities in Europe' in spring 2019.

Aside from these three families that are native to the land, Indo-European, Semitic, Mongolian and Turkic languages (i.e., Russian, Greek, Arabic, Azerbaijani, and Kalmyk) are also used by a decent amount of people. However, since the number of speakers for a majority of the Caucasian languages barely exceeds a couple hundred thousand, extinction is definitely a concern for these communities. For example, the Northeast Caucasian language family has a combined number of less than four million speakers. It is no surprise then, that the Caucasus is a common site for language hotspots (Nichols, 1998), or locations where there is a cluster of endangered languages. UNESCO lists many of the Caucasian languages as “at-risk” (Moseley, 2010) and recent years suggest more Russian hegemony in the future. Despite all of this, the languages of Caucasia demonstrate unique features that continue to drive more linguists to study and record them.

One of the features of Caucasian languages that makes them stand out is their sheer number of consonants. For example, Avar has forty-five distinct consonants and Lezgian has fifty-four (Haspelmath, 1993). This is not uncommon with any of the Northeast Caucasian languages.

In fact, recent research reveals that some languages contain upwards of seventy distinct consonants (Hewitt, 2004). This is in part due to the presence of ejectives, or consonants that are produced when airflow is coming out of the mouth. The sounds are often described as sounding like they are being ‘spit out’, but in reality, the high amount of air pressure that results from the airstream flowing outwards creates a dramatic burst of air, hence the ‘spitting’ feel.

In addition to having many ejectives, the Northeast Caucasian languages are notable for their extensive case systems. A language that has cases, such as the accusative, nominative, ablative, etc. uses different affixes to change the role of the word. In layman’s terms, if you want to indicate possession you would use the genitive case. A direct object requires the accusative case, and so forth.

Many languages have case systems – that is not the rare part. The Northeast Caucasian languages simply blow others out of the water with the sheer amount of cases they possess. Tsez, for instance, has at least sixty-four cases! Most other world languages that are known for their case systems, like Hungarian and Russian, only have eighteen and six grammatical cases, respectively.

The Northwest Caucasian branch, on the other hand, isn’t as intense as its languages don’t have an enormous number of consonants or cases. In fact, this family compares pretty evenly with major world language families. Furthermore, The Kartvelian languages, which make up the last branch, are even more different from the other two families. Georgian, for example, has its proper alphabet, while the Northeast and Northwest Caucasian languages utilize the Cyrillic alphabet. Kartvelian languages also have more speakers, making them more prioritized on a national level.

More recently, the Caucasus has been struggling with revitalization efforts. Newer generations stick to speaking the state language, as it offers more opportunities in career paths and improves the general quality of life. English is even participating in the decrease of younger native speakers of Caucasian languages due to the fact that it is the current lingua franca and, consequently, so widespread. Therefore, the youth finds English essential to learn.

As anything can happen in the long run, it’s important for the Caucasus to promote its minority languages and find ways to integrate them in more aspects of life, rather than just the private sectors. It could be a difficult thing to do since there is just such a vast variety of languages in a relatively small area, however, the longer Russian and other major world languages are being used among the people, the longer it will take to convince them to continue speaking their mother tongue.

References:

Britannica, T. E. (2015, September 11). Dagestan. Retrieved April 18, 2019, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Dagestan-republic-Russia.

Central Intelligence Agency. (1995). Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Caucasus Region. Retrieved from https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/commonwealth/ethnocaucasus.jpg.

Owens, Jonathan (2000). Arabic As a Minority Language. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 89–101. ISBN 9783110165784.

Moseley, Christopher (ed.). 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, 3rd edn. Paris, UNESCO Publishing. Online version: http://www.unesco.org/culture/en/endangeredlanguages/atlas

Haspelmath, M. (1993). A grammar of Lezgian. (Mouton grammar library; 9). Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter. – ISBN 3-11-013735-6, p. 2

Hewitt, George (2004). Introduction to the Study of the Languages of the Caucasus. Munich: Lincom Europaq. p. 49.

Nichols, Johanna. 1998. An overview of languages of the Caucasus. http://popgen.well.ox.ac.uk/eurasia/htdocs/nichols/nichols.html

Emily Sardarov wrote this blog post as a senior in Linguistics in 418 'Language and Minorities in Europe' in spring 2019.

You can walk about the streets of Makhachkala, Russia for five minutes tops and hear a handful of different languages being spoken by the locals. Better yet, take a trip to a smaller selo, or village, like Tagerkent, and you will without a doubt run into somebody who was born in Russia but doesn’t speak a lick of the mother tongue. That’s because perhaps the state language is not their mother tongue. Since both the cities of Makhachkala and Tagerkent are located in Dagestan, a southern Russian republic that is known worldwide for its ethnic, ergo, linguistic diversity (Britannica, 2015), it’s not such a far-fetched situation after all.

|

| https://www.mapsofworld.com/where-is/makhachkala.html |

Historically, Dagestan, meaning “land of mountains” in many of its regional languages, was populated by ethnic peoples who were separated by physical terrain. Consequently, there were long periods of isolation, allowing for the languages to develop for years without interference. Conflict and colonization, however, was inevitable, and as time passed, many kingdoms conquered these lands and left their traces behind in the languages. The evidence lies in the lexicon – Dagestani languages contain many words from Arabic, Turkish, and Persian origins.

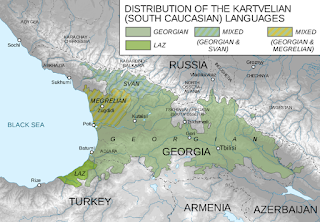

Nowadays, Dagestan makes up part of a larger geographical area, referred to as the Caucasus, that spans from the Black to the Caspian Sea across Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia (C.I.A., 1995). There is a plethora of languages that are indigenous to the Caucasus, and they are split into three branches: Northeast Caucasian, Northwest Caucasian, and Kartvelian. Northeast Caucasian refers to a family of languages that includes Chechen, Avar, Lezgian, etc. Meanwhile, languages such as Adyghe, Abkhaz, Ubykh, and Kabardian constitute the Northwest Caucasian branch, and the Kartvelian language family is comprised of Svan, Georgian, Zan, and other genetically related languages.

Nowadays, Dagestan makes up part of a larger geographical area, referred to as the Caucasus, that spans from the Black to the Caspian Sea across Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia (C.I.A., 1995). There is a plethora of languages that are indigenous to the Caucasus, and they are split into three branches: Northeast Caucasian, Northwest Caucasian, and Kartvelian. Northeast Caucasian refers to a family of languages that includes Chechen, Avar, Lezgian, etc. Meanwhile, languages such as Adyghe, Abkhaz, Ubykh, and Kabardian constitute the Northwest Caucasian branch, and the Kartvelian language family is comprised of Svan, Georgian, Zan, and other genetically related languages.

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kartvelian_languages#/media/File:Kartvelian_languages.svg |

Aside from these three families that are native to the land, Indo-European, Semitic, Mongolian and Turkic languages (i.e., Russian, Greek, Arabic, Azerbaijani, and Kalmyk) are also used by a decent amount of people. However, since the number of speakers for a majority of the Caucasian languages barely exceeds a couple hundred thousand, extinction is definitely a concern for these communities. For example, the Northeast Caucasian language family has a combined number of less than four million speakers. It is no surprise then, that the Caucasus is a common site for language hotspots (Nichols, 1998), or locations where there is a cluster of endangered languages. UNESCO lists many of the Caucasian languages as “at-risk” (Moseley, 2010) and recent years suggest more Russian hegemony in the future. Despite all of this, the languages of Caucasia demonstrate unique features that continue to drive more linguists to study and record them.

One of the features of Caucasian languages that makes them stand out is their sheer number of consonants. For example, Avar has forty-five distinct consonants and Lezgian has fifty-four (Haspelmath, 1993). This is not uncommon with any of the Northeast Caucasian languages.

In fact, recent research reveals that some languages contain upwards of seventy distinct consonants (Hewitt, 2004). This is in part due to the presence of ejectives, or consonants that are produced when airflow is coming out of the mouth. The sounds are often described as sounding like they are being ‘spit out’, but in reality, the high amount of air pressure that results from the airstream flowing outwards creates a dramatic burst of air, hence the ‘spitting’ feel.

In addition to having many ejectives, the Northeast Caucasian languages are notable for their extensive case systems. A language that has cases, such as the accusative, nominative, ablative, etc. uses different affixes to change the role of the word. In layman’s terms, if you want to indicate possession you would use the genitive case. A direct object requires the accusative case, and so forth.

Many languages have case systems – that is not the rare part. The Northeast Caucasian languages simply blow others out of the water with the sheer amount of cases they possess. Tsez, for instance, has at least sixty-four cases! Most other world languages that are known for their case systems, like Hungarian and Russian, only have eighteen and six grammatical cases, respectively.

The Northwest Caucasian branch, on the other hand, isn’t as intense as its languages don’t have an enormous number of consonants or cases. In fact, this family compares pretty evenly with major world language families. Furthermore, The Kartvelian languages, which make up the last branch, are even more different from the other two families. Georgian, for example, has its proper alphabet, while the Northeast and Northwest Caucasian languages utilize the Cyrillic alphabet. Kartvelian languages also have more speakers, making them more prioritized on a national level.

More recently, the Caucasus has been struggling with revitalization efforts. Newer generations stick to speaking the state language, as it offers more opportunities in career paths and improves the general quality of life. English is even participating in the decrease of younger native speakers of Caucasian languages due to the fact that it is the current lingua franca and, consequently, so widespread. Therefore, the youth finds English essential to learn.

As anything can happen in the long run, it’s important for the Caucasus to promote its minority languages and find ways to integrate them in more aspects of life, rather than just the private sectors. It could be a difficult thing to do since there is just such a vast variety of languages in a relatively small area, however, the longer Russian and other major world languages are being used among the people, the longer it will take to convince them to continue speaking their mother tongue.

References:

Britannica, T. E. (2015, September 11). Dagestan. Retrieved April 18, 2019, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Dagestan-republic-Russia.

Central Intelligence Agency. (1995). Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Caucasus Region. Retrieved from https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/commonwealth/ethnocaucasus.jpg.

Owens, Jonathan (2000). Arabic As a Minority Language. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 89–101. ISBN 9783110165784.

Moseley, Christopher (ed.). 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, 3rd edn. Paris, UNESCO Publishing. Online version: http://www.unesco.org/culture/en/endangeredlanguages/atlas

Haspelmath, M. (1993). A grammar of Lezgian. (Mouton grammar library; 9). Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter. – ISBN 3-11-013735-6, p. 2

Hewitt, George (2004). Introduction to the Study of the Languages of the Caucasus. Munich: Lincom Europaq. p. 49.

Nichols, Johanna. 1998. An overview of languages of the Caucasus. http://popgen.well.ox.ac.uk/eurasia/htdocs/nichols/nichols.html

Comments

Post a Comment

The moderators of the Linguis Europae blog reserve the right to delete any comments that they deem inappropriate. This may include, but is not limited to, spam, racist or disrespectful comments about other cultures/groups or directed at other commenters, and explicit language.