by Sophia Ebel

Sophia Ebel is a senior in Comparative Literature and Germanic Studies at the University of Illinois. Her future plans include applying to graduate programs abroad in language education and education policy. She wrote this blog post in 418 'Language and Minorities in Europe' in Fall 2021.

It is not uncommon for tensions to exist between linguistic groups, but in few cases is the relationship as strained as between Yiddish and German. Yiddish is a Germanic language that was previously spoken by Ashkenazi Jewish communities throughout Europe. For sociopolitical reasons Yiddish was historically viewed as a lesser dialect or distorted form of German, despite its lengthy history and unique influences from Hebrew, Aramaic, and the Romance and Slavic language families. Still, prior to the Second World War there were approximately 13 million Yiddish speakers living in Europe (Walfish).

The Holocaust, however, more than decimated this population and many of the surviving Yiddish speakers chose to emigrate and abandon their language as they sought to move forward with their lives. Today there are only an estimated 600,000 Yiddish speakers worldwide, with the majority living either in Israel or in Hasidic and Haredi communities in the United States (Yiddish FAQs). Despite Germany’s linguistic relationship with Yiddish, there are few Yiddish speakers in the country today. Despite this, however, Germany does have a vibrant Klezmer and Yiddish music scene. The backgrounds, motivations, and goals of performers have varied over the past 75 years, but the rise to prominence of this specialized community of practice in post-Holocaust Germany illuminates the complexities of understanding language, identity, and history in the country.

One fascinating aspect of this musical scene and expression of the Yiddish language is that very few of the performers are themselves Jewish or have Yiddish-speaking background (Eckstaedt). This seeming paradox dates back to the years immediately following the Second World War where the younger generation of Germans gravitated towards the genre as they sought to both protest their parents’ generation and their complicity in the Holocaust, and to craft a traditionally grounded musical identity that did not draw from the German folk music used and abused by the Nazi regime. While most of these musicians genuinely developed a deep interest in Yiddish and Judaism, they had no knowledge surrounding how Yiddish and Klezmer music were supposed to sound. They tended to fall into patterns of exoticization and stereotyping, perpetually placing Jews in the role either of the victim or of a folkloric figure belonging purely to the past (Ottens).

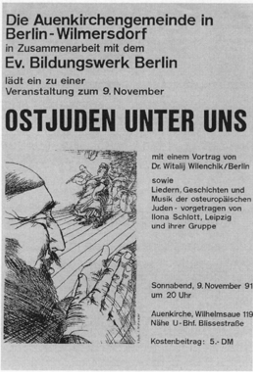

Following German reunification, three diverging trends emerged in German-Yiddish music: authentication, trivialization, and globalization. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 allowed for Jewish musicians from Eastern Europe to come to Germany for the first time. Along with a boom in American Klezmer groups touring Germany in the 1980s and 1990s, these musicians brought authentic knowledge of Klezmer music to Germany, providing old audio recordings of Yiddish and Klezmer for German musicians to learn from. At the same time, however, the increased immigration from Eastern Europe and persistent Antisemitism in Germany led to a parallel Yiddish performance scene reminiscent of minstrel shows in the United States. Non-Jewish Germans would make jokes and sing songs in “Yiddish”, but in their performances reduced the language to merely “verkümmerten Deutsch” [stunted German] and the European Jewish experience to an exotic whirlwind of poverty and persecution (Ottens). By this point though Yiddish and Klezmer were no longer the sole minority musical tradition in Germany. Awareness of world music was also increasing, and Klezmer became simply one form of many used as a symbol for multiculturalism and diversity.

These three trends have converged into two contemporary modes of Yiddish and Klezmer performance. The first draws on authenticity and is enabled by globalization; it is grounded in the past, Eastern European Jewish culture, and focused on maintaining Klezmer’s traditional style and language. The second operates in a framework of globalization yet has been criticized for perpetuating trivializing elements; it redefines Klezmer as an expression of spirituality rather than a fixed musical style and expands the genre to potentially any musical output (Loentz). Both of these modes, however, are dominated by non-Jews and often push Jews to their periphery. This raises questions of the extent to which language and culture can be separated from identity, and where the line should be drawn between the appreciation and appropriation of the Yiddish language and culture.

On the one hand, proponents of broadening definitions and expressions of Klezmer and Yiddish music argue that it makes the form more accessible and facilitates learning about Jewish and Yiddish culture. This emphasis on learning is also shared by the more traditionalist school. Aaron Eckstaedt accordingly describes Klezmer music and Yiddish as “a unique chance [for Germans] to grasp something Jewish” in a country where few Jews remain but learning about Judaism and German-Jewish history have become an important part of national identity (Eckstaedt 46). Others argue, however, that contemporary Yiddish and Klezmer music in Germany are less “Jewish” than they are representations of Germany’s post-WWII cultural landscape. Germany’s history adds a problematizing slant to this phenomenon: does the country responsible for destroying a language and culture get to recreate it as an expression of interest and tolerance? Does this cultural shift mark how far Germany has come, or is it simply a second erasure of Jewish language and culture in the country?

References

Eckstaedt, Aaron. “Yiddish Folk Music as a Marker of Identity in Post-War Germany,” European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe, vol. 43, no. 1, Spring 2010, pp. 37-47.

Loentz, Elizabeth. “Yiddish, Kanak Sprak, Klezmer, and HipHop: Ethnolect, Minority Culture, Multiculturalism, and Stereotype in Germany,” Shofar, vol. 25, no. 1, Fall 2006, pp. 33-62.

Ottens, Rita. “Der Klezmer als Ideologischer Arbeiter: Jiddische Musik in Deutschkland,” Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik, vol. 159, no. 3, May-June 1998, pp. 26-29.

Walfish, Mordecai. “The History of Yiddish,” My Jewish Learning, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/yiddish/.

“Yiddish FAQs,” Rutgers University Department of Jewish Studies, https://jewishstudies.rutgers.edu/yiddish/102-department-of-jewish-studies/yiddish/159-yiddish-faqs.

Comments

Post a Comment

The moderators of the Linguis Europae blog reserve the right to delete any comments that they deem inappropriate. This may include, but is not limited to, spam, racist or disrespectful comments about other cultures/groups or directed at other commenters, and explicit language.